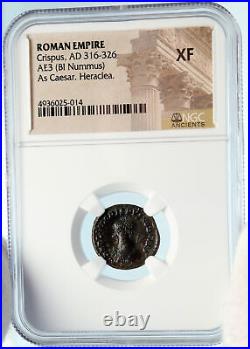

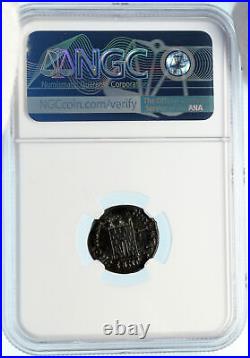

CRISPUS Authentic Ancient 317AD CAMP GATE Roman Coin NGC Certified i83598

Item: i83598 Authentic Ancient Coin of. Bronze AE3 17mm (2.81 grams) Heraclea mint, struck circa 317 A. RIC VII 44 (number of dots) Certification: NGC Ancients. XF 4936025-014 D N F L IVL CRISPVS NOB CAES, laureate bust left with mappa, globe and scepter.

PROVIDENTIAE CAESS, camp gate with three turrets; mintmark two dots in right field and SMHG in exergue. A military camp or bivouac is a semi-permanent facility for the lodging of an army.

Camps are erected when a military force travels away from a major installation or fort during training or operations, and often have the form of large campsites. In the Roman era the military camp had highly stylized parameters and served an entire legion. Archaeological investigations have revealed many details of these Roman camps at sites such as Vindolanda (England) and Raedykes (Scotland). The Latin word castra , with its singular castrum , was used by the ancient Romans to mean buildings or plots of land reserved to or constructed for use as a military defensive position. The word appears in both Oscan and Umbrian (dialects of Italic) as well as in Latin.In classical Latin the word castra always means "great legionary encampment", both "marching", "temporary" ones and the "fortified permanent" ones, while the diminutive form castellum was used for the smaller forts, which were usually, but not always, occupied by the auxiliary units and used as logistic bases for the legions, as explained by Vegetius. A generic term is praesidium ("guard post or garrison"). The terms stratopedon ("army camp") and phrourion ("fort") were used by Greek language authors, in order to designate the Roman castra and the Roman castellum respectively.

In English, the terms "Roman fortress", "Roman fort" and "Roman camp" are commonly used for the castra. However the scholars' convention always requires the use of the word "camp", "marching camp" and "fortress" as a translation of castra and the use of the word "fort" as a translation of castellum and this type of convention is usually followed and found in all the scholarly works. And Helena the Younger wife of Julian II. Flavius Julius Crispus, also known as Flavius Claudius Crispus and Flavius Valerius Crispus was a Caesar of the Roman Empire. He was the first-born son of Constantine I and Minervina.

Crispus' year and place of birth are uncertain. He is considered likely to have been born between 299 and 305, somewhere in the Eastern Roman Empire. His mother Minervina was either a concubine or a first wife to Constantine. Nothing else is known about Minervina. His father served as a hostage in the court of Eastern Roman Emperor Diocletian in Nicomedia. Thus securing the loyalty of Caesar of the Western Roman Empire Constantius Chlorus, father of Constantine and grandfather of Crispus. In 307, Constantine allied to the Italian Augusti, and this alliance was sealed with the marriage of Constantine to Fausta, daughter of Maximian and sister of Maxentius. The marriage of Constantine to Fausta has caused modern historians to question the status of his relation to Minervina and Crispus. If Minervina was his legitimate wife, Constantine would have needed to secure a divorce before marrying Fausta.This would have required an official written order signed by Constantine himself, but no such order is mentioned by contemporary sources. This silence in the sources has led many historians to conclude that the relationship between Constantine and Minervina was informal and to assume her to have been an unofficial lover. However, Minervina may have already been dead by 307. A widowed Constantine would need no divorce order. Neither the true nature of the relationship between Constantine and Minervina nor the reason Crispus came under the protection of his father will ever probably be known.

The offspring of an illegitimate affair could have caused dynastical problems and would likely be dismissed, but Crispus was raised by his father in Gaul. This can be seen as evidence of a loving and public relationship between Constantine and Minervina which gave him a reason to protect her son. The story of Minervina is quite similar to that of Constantine's mother Helena. Constantine's father later had to divorce her for political reasons, specifically, to marry Flavia Maximiana Theodora, the daughter of Maximian, in order to secure his alliance with his new father-in-law. Constantine in turn may have had to put aside Minervina in order to secure an alliance with the same man.

Constantius did not however dismiss Constantine as his son, and perhaps Constantine chose to follow the example of his father. Whatever the reason, Constantine kept Crispus at his side. Surviving sources are unanimous in declaring him a loving, trusting and protective father to his first son. Constantine even entrusted his education to Lactantius, among the most important Christian teachers of that time, who probably started teaching Crispus before 317.By 317, there were two remaining Augusti in control of the Roman Empire. Constantine reigned as an Western Roman Emperor and his brother-in-law Licinius as an Eastern Roman Emperor. On 1 March 317, the two co-reigning Augusti jointly proclaimed three new Caesars.

Crispus alongside his younger half-brother Constantine II and his first cousin Licinius iunior. Constantine II was the older son of Fausta but was probably about a month old at the time of his proclamation. Constantine apparently believed in the abilities of his son and appointed Crispus as Commander of Gaul. The new Caesar soon held residence in Augusta Treverorum (modern Trier), regional capital of Germania.In January 322, Crispus was married to a young woman called Helena. Helena bore him a son in October, 322. There is no surviving account of the name or later fate of the son. Eusebius of Caesarea reported that Constantine was proud of his son and very pleased to become a grandfather.

Crispus was leader in victorious military operations against the Franks and the Alamanni in 318, 320 and 323. Thus he secured the continued Roman presence in the areas of Gaul and Germania.Crispus joined his father in visiting Rome during 322, and received the warmest and most enthusiastic welcome by the crowds. The soldiers adored him thanks to his strategic abilities and the victories to which he had led the Roman legions. Crispus spent the following years assisting Constantine in the war against by then hostile Licinius. In 324, Constantine appointed Crispus as the commander of his fleet which left the port of Piraeus to confront the rival fleet of Licinius. The subsequent Battle of Hellespont was fought in at the straits of Bosporus.

Thus Crispus achieved his most important and difficult victory which further established his reputation as a brilliant soldier and general. Following his navy activities, Crispus was assigned part of the legions loyal to his father. The other part was commanded by Constantine himself.

Crispus led the legions assigned to him in another victorious battle outside Chrysopolis against the armies of Licinius. The two victories were his contribution to the final triumph of his father over Licinius. Constantine was the only Augustus left in the Empire. He honoured his son for his support and success by depicting his face in imperial coins, statues, mosaics, cameos, etc. Eusebius of Caesaria wrote for Crispus that he is an Imperator most dear to God and in all regards comparable to his father. Crispus was the most likely choice for an heir to the throne at the time. His siblings Constantine II, Constantius II and Constans were far too young and inexperienced. In 326, Crispus life came to a sudden end: on his father's orders, he was tried by a local court at Pola, Istria, condemned to death and executed. Soon afterwards, Constantine had his own wife, Fausta, killed; she was suffocated in an over-heated bath. The reason for this act remains unclear and historians have long debated Constantine's motivation. Zosimus in the 5th century and Joannes Zonaras in the 12th century both reported that Fausta, stepmother of Crispus, was extremely jealous of him. She was reportedly afraid that Constantine would put aside the sons she bore him. So, in order to get rid of Crispus, Fausta set him up. She reportedly told the young Caesar that she was in love with him and suggested an illegitimate love affair.Crispus denied the immoral wishes of Fausta and left the palace in a state of a shock. Then Fausta said to Constantine that Crispus had no respect for his father, since the Caesar was in love with his father's own wife. She reported to Constantine that she dismissed him after his attempt to rape her.

Constantine believed her and, true to his strong personality and short temper, executed his beloved son. A few months later, Constantine reportedly found out the whole truth and then killed Fausta. This version of events has become the most widely accepted, since all other reports are even less satisfactory.That Fausta and Crispus could have plotted treason against Constantine is rejected by most historians. As they would have nothing to gain considering their positions as favourites of Constantine.

In any case, such a case would not have been tried by a local court as Crispus' case clearly was. Another view suggests that Constantine killed Crispus because as an supposedly illegitimate son, he would cause a crisis in the order of succession to the throne.

However, Constantine had kept him at his side for twenty years without any such decision. Constantine also had the authority to appoint his younger, legitimate sons as his heirs. Some reports claimed that Constantine was envious of the success of his son and afraid of him. This seems improbable, given that Constantine had twenty years of experience as emperor while Crispus was still a young Caesar. Similarly, there seems to be no evidence that Crispus had any ambitions to harm or displace his father.So while the story of Zosimus and Zonaras seems the most believable one, there are also problems relating to their version of events. Constantine's reaction suggests that he suspected Crispus of a crime so terrible that death was not enough. Crispus also suffered damnatio memoriae, meaning his name was never mentioned again and was deleted from all official documents and monuments.

Crispus, his wife Helena and their son were never to be mentioned again in historical records. The eventual fate of Helena and her son is a mystery.

Constantine did not restore his son's innocence and name, as he probably would have on learning of his son's innocence. Perhaps Constantine's pride, or shame at having executed his son, prevented him from publicly admitting having made a mistake. It is beyond doubt that there was a connection between the deaths of Crispus and Fausta. Such agreement among different sources connecting two deaths is extremely rare in itself. A number of modern historians have suggested that Crispus and Fausta really did have an illegitimate affair. When Constantine found out, his reaction was to have both of them killed. What delayed the death of Fausta may have been a pregnancy. Since the years of birth for the two known daughters of Constantine and Fausta remain unknown, one of their births may have delayed their mother's execution. The story of Zosimus and Zonaras listed above is suspiciously similar to both the legend of Hippolytus of Athens (casting Crispus in the role of the youth, Constantine in the role of Theseus and Fausta in the role of Phaedra) as well as the Biblical account of Joseph and Potiphar's wife. World-renowned expert numismatist, enthusiast, author and dealer in authentic ancient Greek, ancient Roman, ancient Byzantine, world coins & more. Ilya Zlobin is an independent individual who has a passion for coin collecting, research and understanding the importance of the historical context and significance all coins and objects represent.Send me a message about this and I can update your invoice should you want this method. Getting your order to you, quickly and securely is a top priority and is taken seriously here. Great care is taken in packaging and mailing every item securely and quickly. What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic? You will be very happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing.

Additionally, the coin is inside it's own protective coin flip (holder), with a 2x2 inch description of the coin matching the individual number on the COA. Whether your goal is to collect or give the item as a gift, coins presented like this could be more prized and valued higher than items that were not given such care and attention to. When should I leave feedback? Please don't leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens sometimes that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for their order to arrive. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me.

My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service. How and where do I learn more about collecting ancient coins?

Visit the Guide on How to Use My Store. For on an overview about using my store, with additional information and links to all other parts of my store which may include educational information on topics you are looking for. This item is in the category "Coins & Paper Money\Coins: Ancient\Roman: Imperial (27 BC-476 AD)". The seller is "highrating_lowprice" and is located in this country: US.This item can be shipped worldwide.

- Certification Number: 4936025-014

- Certification: NGC

- Grade: XF

- Ruler: Crispus

- Denomination: Denomination_in_description

- Year: Year_in_description